Stomach Anatomy

- Introduction

- Importance of Stomach in Surgery

- Some Challenges in Understanding Stomach Anatomy

- Anatomical Relations of Stomach (Surrounding Structures)

- Parts of the Stomach

- Important Definitions In Stomach Anatomy

- Angle of His (Incisura Cardialis)

- Incisura Angularis

- Lesser Curvature (Curvatura Minor)

- Greater Curvature (Curvatura Major)

- Gastrocolic Omentum (Gastrocolic Ligament)

- Omentum Minus (Lesser Omentum)

- Omentum Majus (Greater Omentum, Gastrocolic Omentum, Epiploon)

- Peritoneal (Abdominal) Cavity

- Peritoneal Ligaments

- Embryology of the Stomach

- Arteries of the Stomach

- Veins of the Stomach

- Clinical Significance of Rich Blood Supply to the Stomach

- Innervation of the Stomach

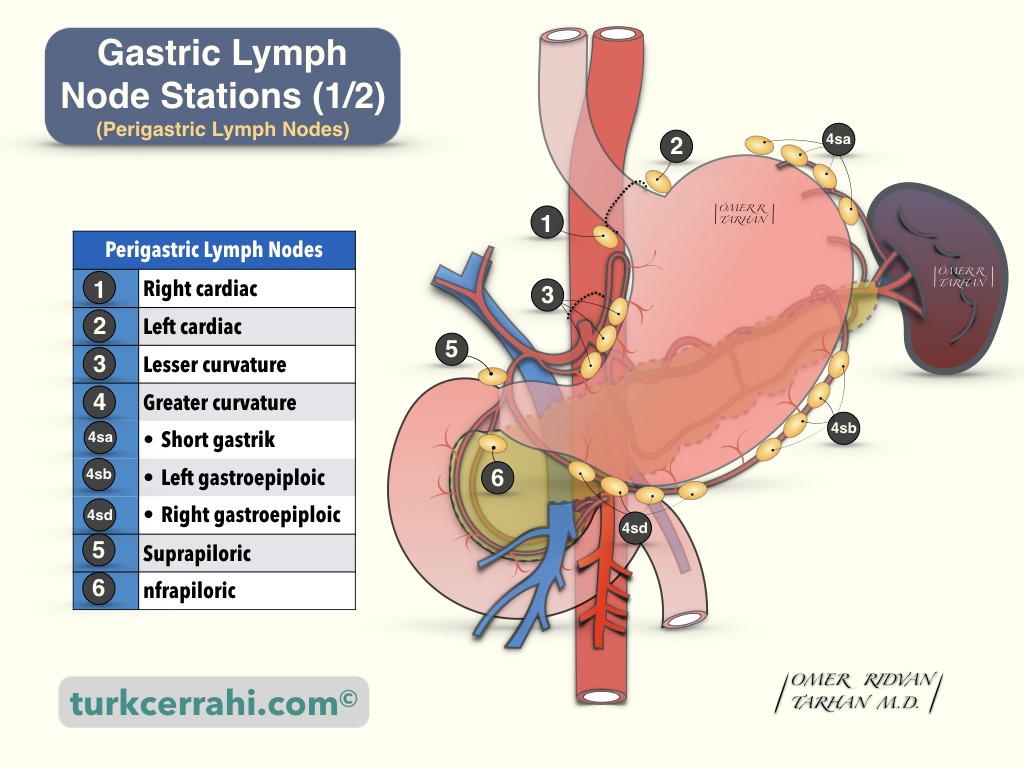

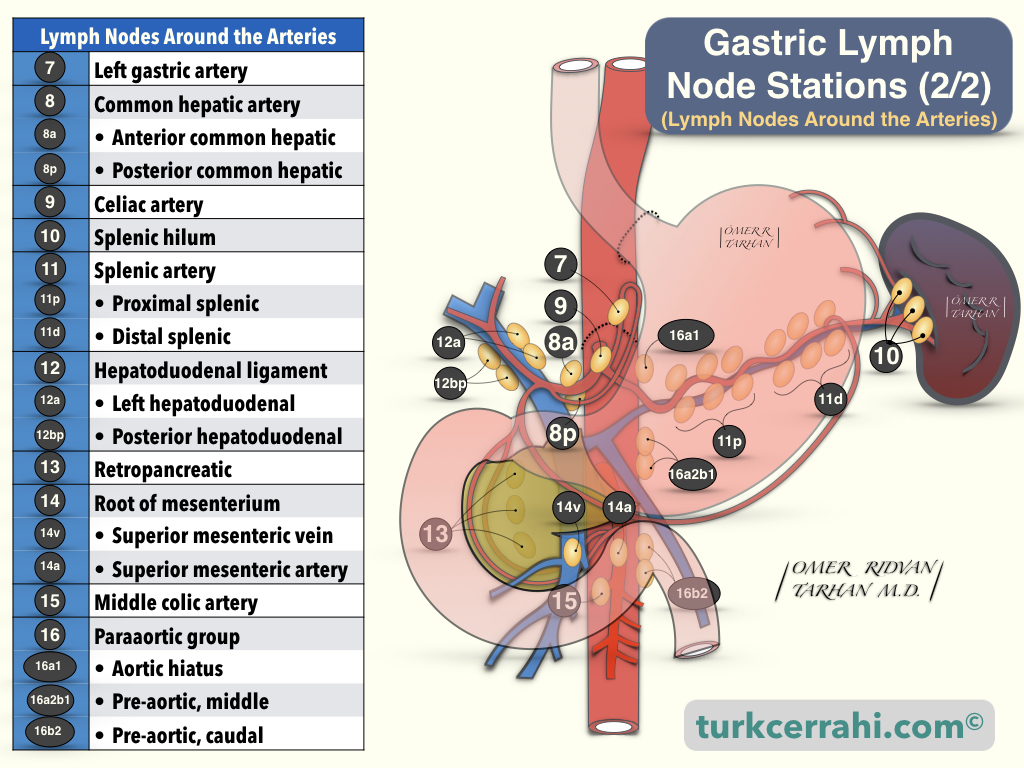

- Lymphatic Drainage of the Stomach

- Histology of the Stomach

1. Introduction

The stomach is an expandable organ of the digestive system, consisting of muscles. The stomach is located between the esophagus and the duodenum. The stomach is in the left upper part of the abdominal cavity. It functions in the second phase of digestion (following chewing).

The stomach physically (peristalsis) and chemically (acid, protease enzymes, pepsin) breaks down food. The proximal part of the stomach (fundus, corpus) stores food, while the distal part (antrum) mixes and grinds it. The result is a semi-liquid material (chyme).

There are sphincters at the entrance and exit of the stomach. Of these, the lower esophageal sphincter prevents the stomach contents from escaping back into the esophagus (most importantly, stomach acid), while the pyloric sphincter allows the partially digested food (chyme) to flow slowly from the stomach to the small intestine.

The rate of gastric emptying depends on whether the food is solid or liquid (particle size), osmolarity, caloric content, and fat content. The stomach drains liquid foods faster than solids. The half-emptying time of water in the stomach is approximately 12 minutes, and the solids take approximately 2 hours. For example, when we drink 200 ml of water, 100 ml of it passes into the duodenum after 12 minutes. As the calorie, osmolarity, and fat ratio of the food increases, the emptying of the stomach slows down.

Although nutrients are absorbed by the small intestine, some substances are also absorbed by the stomach. These substances are;

- Water; especially in dehydration

- Aspirin

- Amino acids

- Ethanol. 10-20 percent of the alcohol in alcoholic beverages

- Caffeine

- A small amount of water-soluble vitamins (non-ADEK vitamins)

Digestive juices and mucus are secreted from the mucous membrane lining the stomach. The gastric mucosa is smooth, soft, and velvety in appearance, and, when viewed closely, its surface has many pits (gastric pittings). As a result, in scanning electron microscopy, the surface of the gastric mucosa resembles the surface of a sponge. These pits are the holes where the stomach glands are opened. The differentiated (various) cells of the gastric glands produce many important secretions: digestive enzymes, hormones, hydrochloric acid, and intrinsic factor. The intrinsic factor is essential for the absorption of vitamin B12 from the last part of the small intestine. The gastric mucosa also produces a sticky, alkaline-basic mucus to protect itself from the acid produced by its own.

2. Importance of Stomach in Surgery

Benign stomach diseases such as peptic ulcers, gastritis, and gastric cancer are very common in the community. Furthermore, since the anatomy and physiology of the stomach are changed after gastric surgeries, postgastrectomy syndromes are frequently encountered (For example; dumping syndrome, diarrhea, gastric stasis, alkaline reflux gastritis, roux syndrome, gallstones, weight loss, anemia).

3. Some Challenges in Understanding Stomach Anatomy

- Controversial definitions. For example, cardia, gastroesophageal junction, antrum, pylorus.

- Inadequate understanding of gastrointestinal tract embryology.

- Confusing embryological cross-section drawings. Some drawings show the top view, others the bottom view. Furthermore, the right-left / up-down directions of the drawings are different or unspecified. However, many medical professionals are familiar with viewing from below a cross-sectional image of the body in the supine position (lying on their back), as in computed tomography cross-sectional views.

- Giving a structure more than one name (although not as much as inguinal anatomy).

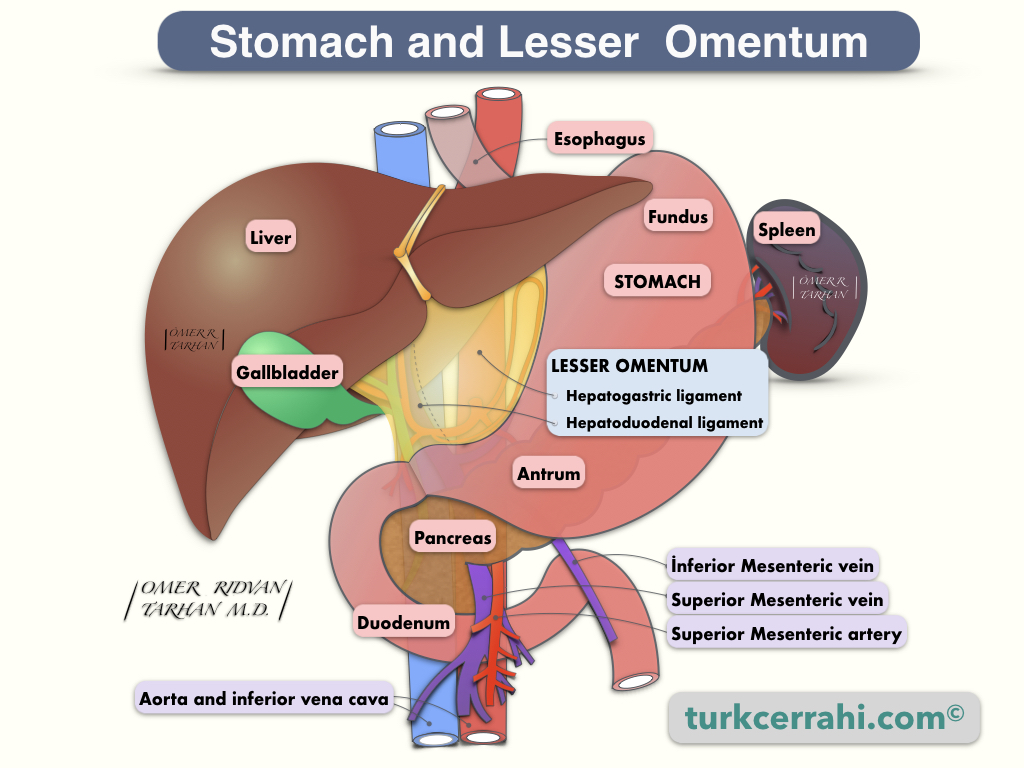

4. Anatomical Relations of Stomach (Surrounding Structures)

- The stomach is surrounded by the liver, transverse colon, pancreas, and spleen.

- The left lobe of the liver (lateral segment (segment 2-3)) covers the anterior surface of the stomach. The stomach (lesser curvature) is connected to the liver by the hepatogastric ligament.

- At the lower edge of the stomach is the transverse colon (connected by the gastrocolic ligament).

- The posterior surface of the stomach is adjacent to the left hemidiaphragm above, left kidney and adrenal gland, pancreas, aorta, and celiac trunk below.

- The spleen is located in the left upper part of the stomach.

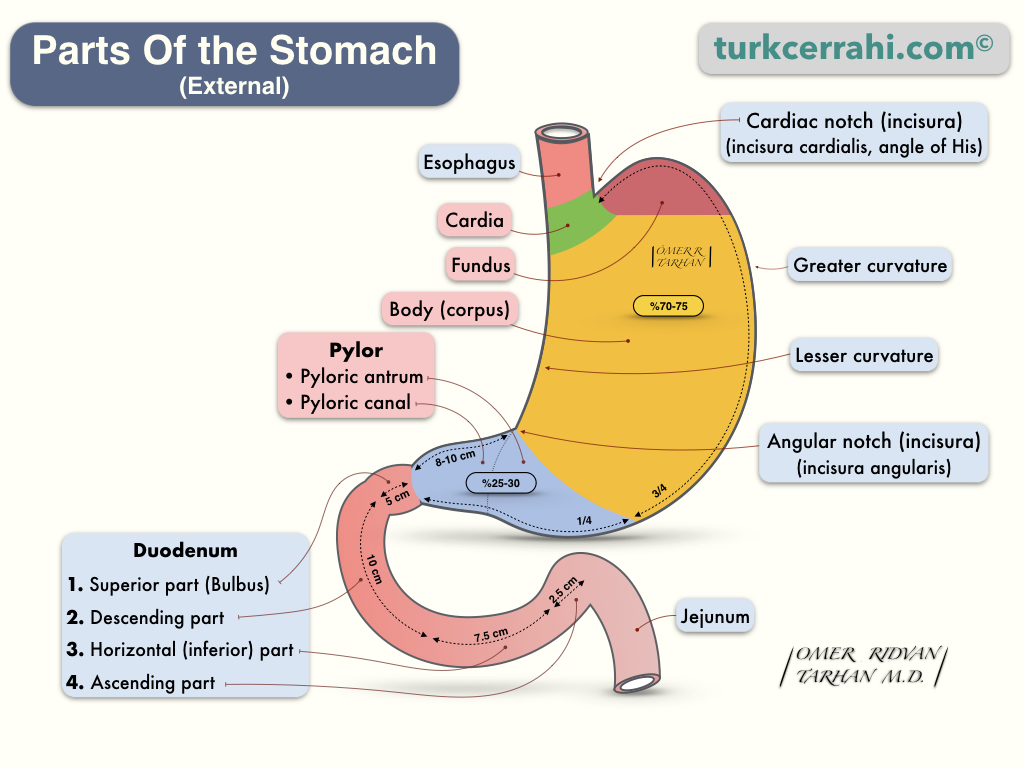

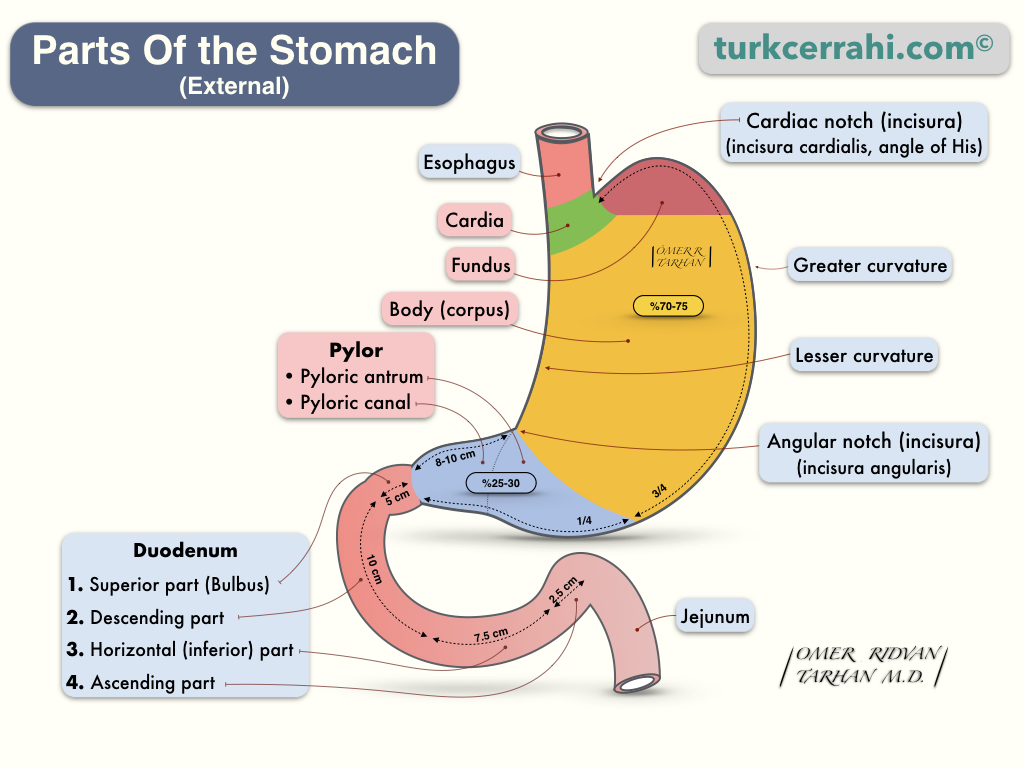

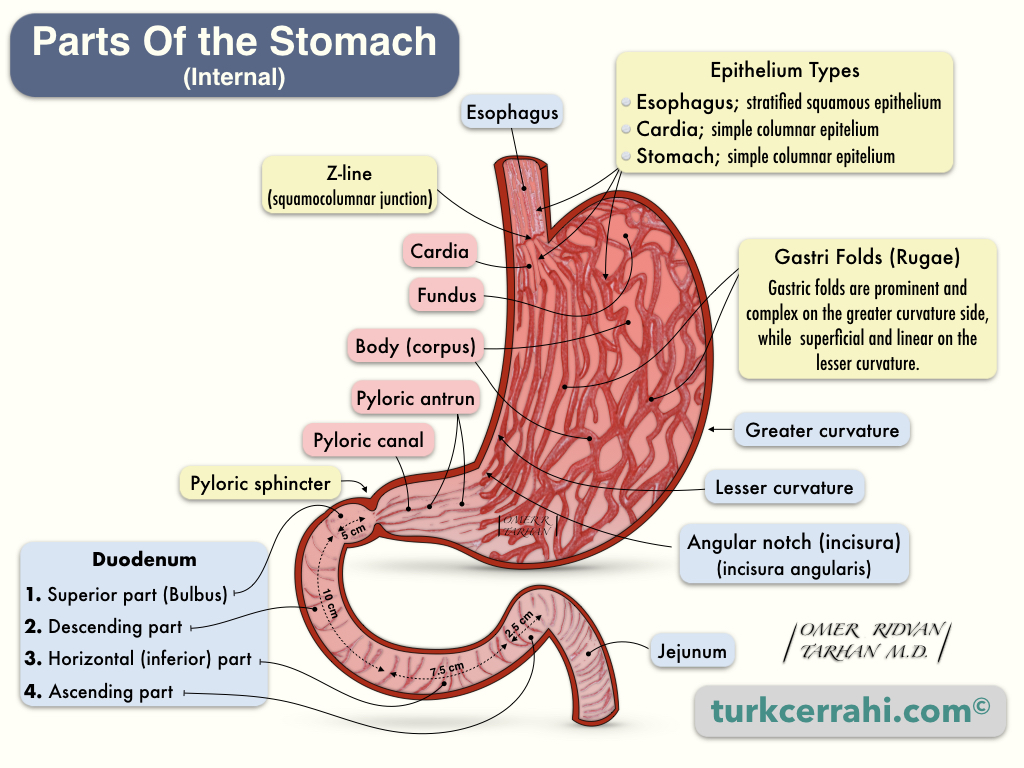

5. Parts of the Stomach

Cardia

The cardia can be defined in two ways. The first is the part where the esophagus opens into the stomach (the opening), and the other is the part of the stomach adjacent to this opening. More often, the second meaning is used: it is a very small part of the stomach. It is also called the ostium cardiacum.

Fundus (Fundus Gastricus)

The fundus is the uppermost part of the stomach that is mobile and expandable. The diaphragm is superior to the stomach, and the spleen is to the left. The lower boundary of the fundus is at the level of the gastroesophageal junction (GE junction), then the corpus begins.

Corpus (Corpus Gastrica)

The right side of the corpus is called the lesser curvature, and the left side is called the greater curvature. Curvature (-a) means curve in geometry. The lesser curvature is flatter, and the greater curvature is more curved. The corpus is the largest part of the stomach.

The incisura angularis (angular notch) on the lesser curvature is the boundary between the corpus and antrum; at the greater curvature, this margin is not clear. On the greater curvature, the border is considered to be 1/4 distance from the pylorus.

Pylorus (Pars Pylorica)

Pylorus is the distal part of the stomach that accounts for 25-30% of the stomach's volume. Pylorus has two parts.

- Antrum (Antrum Pylorica)

- Pyloric Canal (Canalis Pylorica)

6. Important Definitions In Stomach Anatomy

Angle of His (Incisura Cardialis)

It is the narrow-angle between the esophagus and the fundus. The fundus is normally gas-filled and can be seen on direct radiographs. This narrow angle between the His and the gas-filled fundus keeps the cardia closed (like a check valve). As a result, gastroesophageal reflux is prevented. Since this angle is flattened in sliding hernias, it is thought that reflux develops.

The angle of His is not fully developed in newborns, so it is natural for these babies to have physiological reflux, vomit easily, and pass gas. The angle of his His develops after 6 months.

Incisura Angularis

Incisura angularis is the point where the lesser curvature turns sharply to the right and the antrum begins.

Lesser Curvature (Curvatura Minor)

The right (medial) border of the stomach, where the omentum minus attaches, has the lesser curvature. It starts from the cardia and continues to the pylorus.

Greater Curvature (Curvatura Major)

The greater curvature is on the left border of the stomach. The splenogastric ligament and the greater omentum are attached to the greater curvature.

Gastrocolic Omentum (Gastrocolic Ligament)

The gastrocolic ligament is part of the greater omentum. It connects the greater curvature of the stomach with the transverse colon. When the gastrocolic ligament is opened, the bursa omentalis (lesser sac) is entered. In other words, the posterior wall of the stomach and the pancreas are reached. For example, in gastric injuries and distal pancreatectomy, the gastrocolic ligament is opened to examine the stomach's posterior wall.

Omentum Minus (Lesser Omentum)

The omentum minus is a two-layer peritoneal structure found between the liver, lesser curvature, and proximal duodenum. The omentum minus is attached to the porta hepatis. The hilum of the liver, or porta hepatis, is a large fissure between the caudate and quadrate lobes through which the hepatic artery proper, portal vein, hepatic duct, and obliterated umbilical vein run.

The omentum minus consists of two parts

- The hepatogastric ligament

- The hepatoduodenal ligament

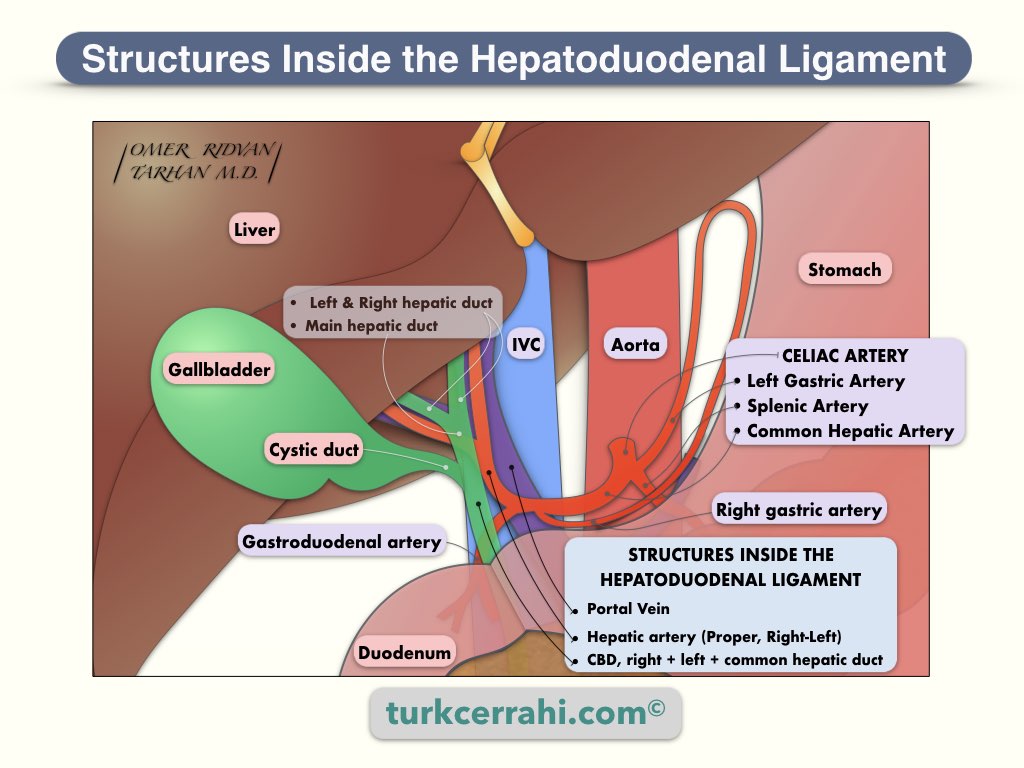

Hepatoduodenal Ligament

The hepatoduodenal ligament, which contains the common bile duct, hepatic artery, portal vein, lymphatics, and nerves, is an important structure. Behind the hepatoduodenal ligament is a passage to the bursa omentalis (foramen Winslow, foramen epiploica). The relationship between these three structures is as follows: the common bile duct is on the right anterior, the hepatic artery is on the left of the common bile duct, and behind these two is the portal vein.

Hepatogastric (Gastrohepatic) Ligament:

The hepatogastric ligament includes the left gastric artery and vein. Because these vessels run close and parallel to the lesser curvature, the hepatogastric ligament can be incised in the middle without causing any damage to these vessels. By opening the gastrohepatic ligament, the bursa omentalis is reached. The mobile and loose lower and middle part of the hepatogastric ligament is called the pars flaccida, and the tight upper part, close to the cardia, is called the pars condensa. The hepatogastric ligament consists of two layers of the peritoneum.

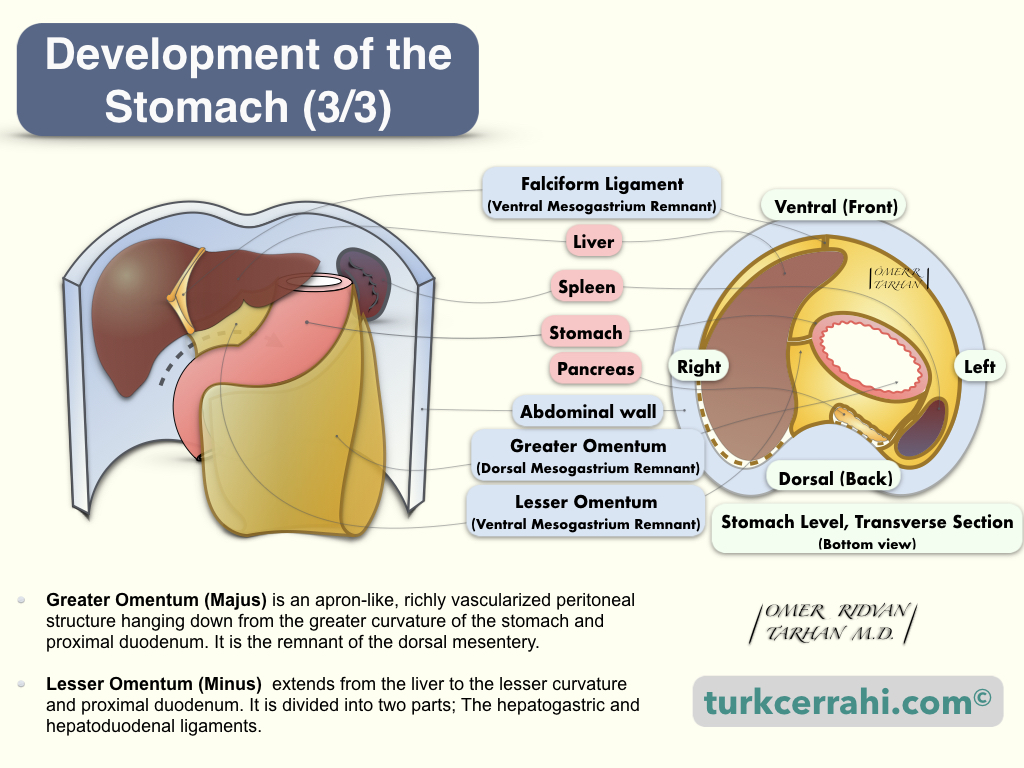

Omentum Majus (Greater Omentum, Gastrocolic Omentum, Epiploon)

The omentum majus is a fatty and vascular peritoneal structure that hangs down from the stomach (great curvature) and resembles a kitchen apron. In many people, it is large enough to cover both the small and large intestines. Therefore, it is the first structure seen when the abdomen is opened. The greater omentum is supplied by the right and left gastroepiploic vessels. Gastroepiploic vessels run in the gastrocolic ligament, and the descending branches continue along with the omentum.

Gastrocolic Ligament

The gastrocolic ligament is a part of the greater omentum that suspends the transverse colon on the stomach's greater curvature. The gastrocolic ligament is bound to the infero-anterior portion of the bursa omentalis. Dividing the gastrocolic ligament allows access to the bursa omentalis, pancreas, and posterior wall of the stomach.

Peritoneal (Abdominal) Cavity

The peritoneal (abdominal) cavity is divided into two parts:

- Greater sac

- Lesser sac (bursa omentalis).

Lesser Sac (Omental Bursa)

The lesser sac, also known as the omental bursa, is a small peritoneal cavity located behind the stomach and lesser omentum.

Borders of Lesser Sac

- Anterior Wall: Lesser omentum, posterior wall of the stomach, greater omentum (under the stomach).

- Posterior Wall

- Superiorly; diaphragm

- Middle; pancreas, left kidney, and adrenal gland in the middle

- Inferiorly; horizontal part of the duodenum (via the peritoneum covering them) and transverse mesocolon.

Greater Sac

The peritoneal cavity remaining outside of the lesser sac is called the greater sac. In everyday medical practice, the greater sac is referred to as the abdominal cavity or peritoneal cavity. The greater sac is divided into supra and infracolic compartments.

Foramen Winslow

The omental foramen (Winslow foramen) is the passage between the greater and lesser sacs.

Borders of Foramen Winslow

- Anteriorly: Free edge of lesser omentum (hepatoduodenal ligament; includes common bile duct, hepatic artery, and portal vein).

- Posteriorly: Inferior vena cava

- Superiorly: Caudate lobe of liver

- Inferiorly: Proximal duodenum, proximal part of the hepatic artery (before it turns up)

Peritoneal Ligaments

Since most of the peritoneal ligaments are attached to the stomach, it is beneficial to learn. The peritoneal ligaments consist of two layers of peritoneum. It comes from one organ and attaches to the other, or the abdominal wall. In other words, peritoneal ligaments connect organs or the abdominal wall.

Suspensory Ligaments of Liver

- Right triangular ligament

- Left triangular ligament

- Falciform ligament

- Round ligament (Ligamentum Teres Hepatis; it is the free edge of the falciform ligament and contains the remnant of the umbilical vein)

Peritoneal Ligaments of the Stomach

- Lesser omentum

- Hepatogastric ligament

- Hepatoduodenal ligament

- Gastrophrenic ligament (phreno gastric ligament)

- Gastrosplenic ligament (great curvature-splenic hilum)

- Greater omentum

- Gastrocolic ligament

- Splenorenal ligament

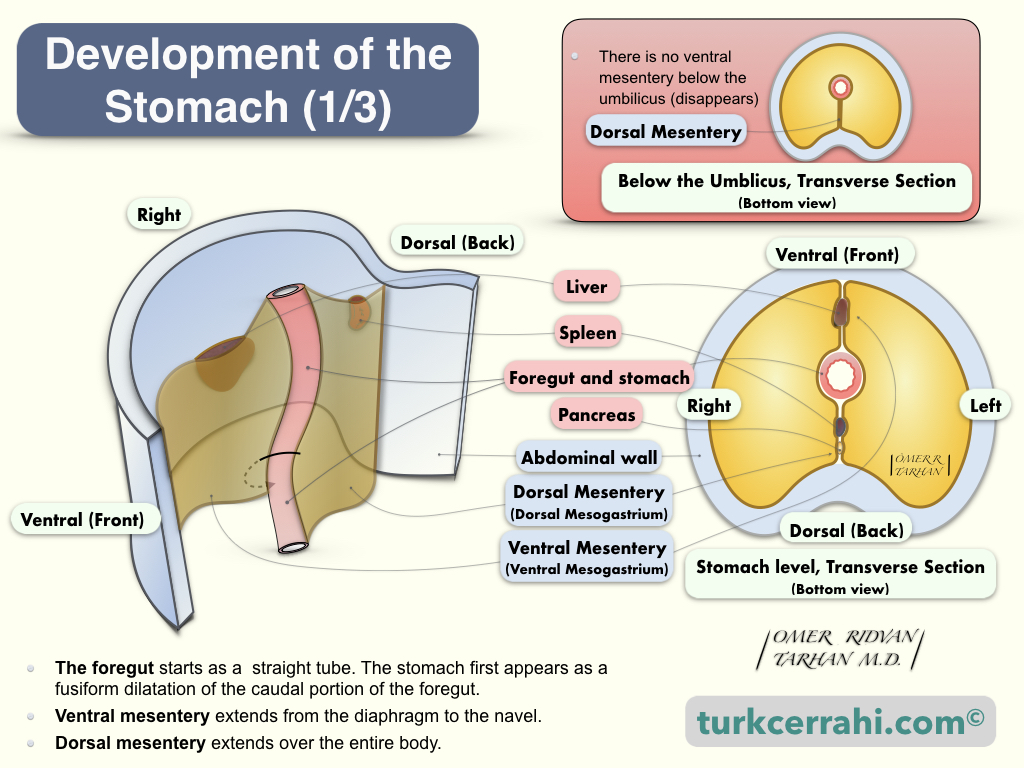

7. Embryology of the Stomach

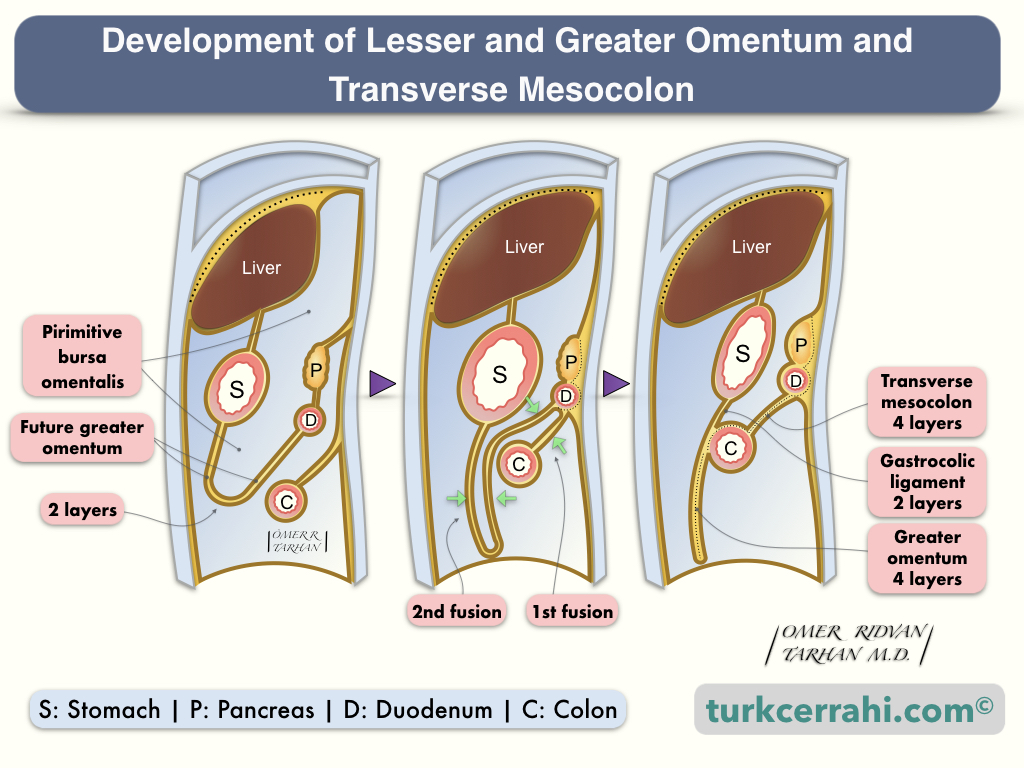

Why is Greater Omentum Composed of 4 Layers of Peritoneum While Lesser omentum 2 Layers?

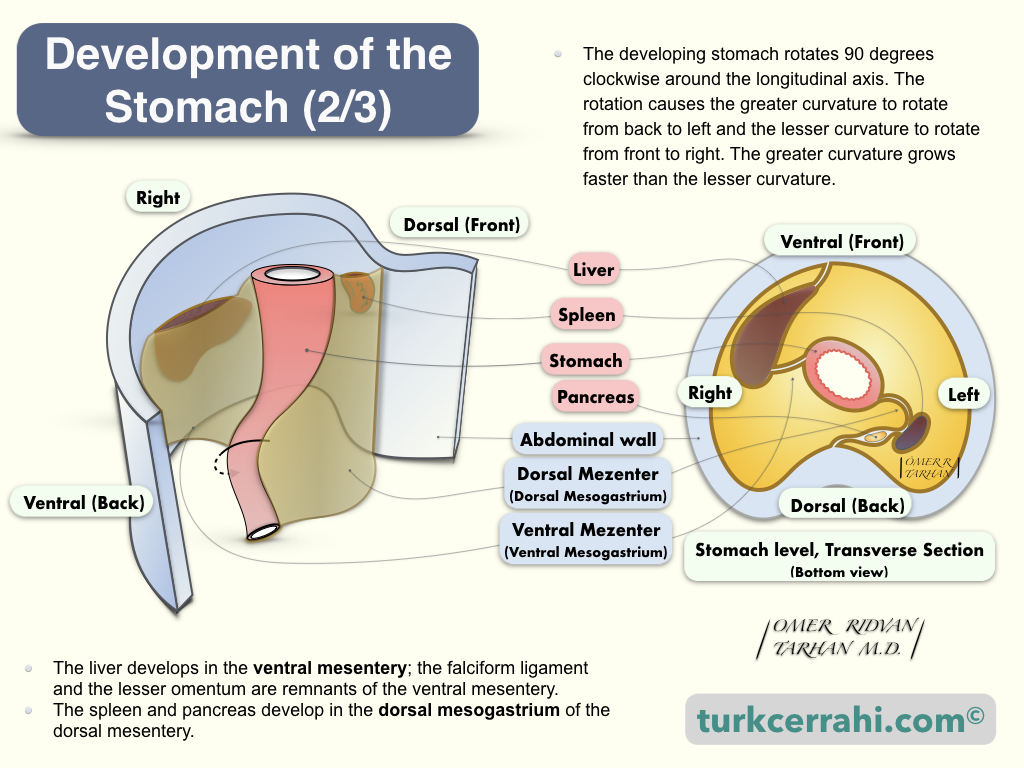

To understand this, let's remember the embryological development of the stomach. The greater omentum develops from the dorsal mesentery, while the lesser omentum develops from the ventral mesentery.

The foregut, from which the stomach also develops, was formerly a straight tube (embryo). This tube is connected to the body anteriorly by the ventral mesentery and posteriorly by the dorsal mesentery.

The ventral mesentery extends from the diaphragm to the umbilicus. The two-layered ventral mesentery is situated just above the umbilical vein, between the future stomach (and proximal duodenum) and the anterior abdominal wall. In addition, the liver develops between these two layers. The falciform ligament and lesser omentum are remnants of the ventral mesentery.

The dorsal mesentery runs alongside the entire trunk. The dorsal mesentery is divided into four sections:

- The dorsal mesogastrium (great omentum, stomach)

- The dorsal mesoduodenum

- The mesentery proper (mesentery of the jejunum and ileum)

- The dorsal mesocolon.

The greater omentum begins as an extension of the peritoneum at the greater curvature of the stomach's anterior and posterior surfaces and descends inferiorly over the transverse colon as a double-layered peritoneum.

The double-layered peritoneum folds posteriorly and ascends to form the four-layered greater omentum, which covers the jejunum and ileum. The double-layered peritoneum then passes in front of the transverse colon again and divides up and down at the level of the horizontal part of the duodenum. The peritoneum layers then continue to cover the retroperitoneal organs and the posterior abdominal wall.

The lesser omentum starts from the lesser curvature of the stomach (anterior and posterior peritoneal layers of the stomach) and attaches to the liver (porta hepatis and ligamentum venosum).

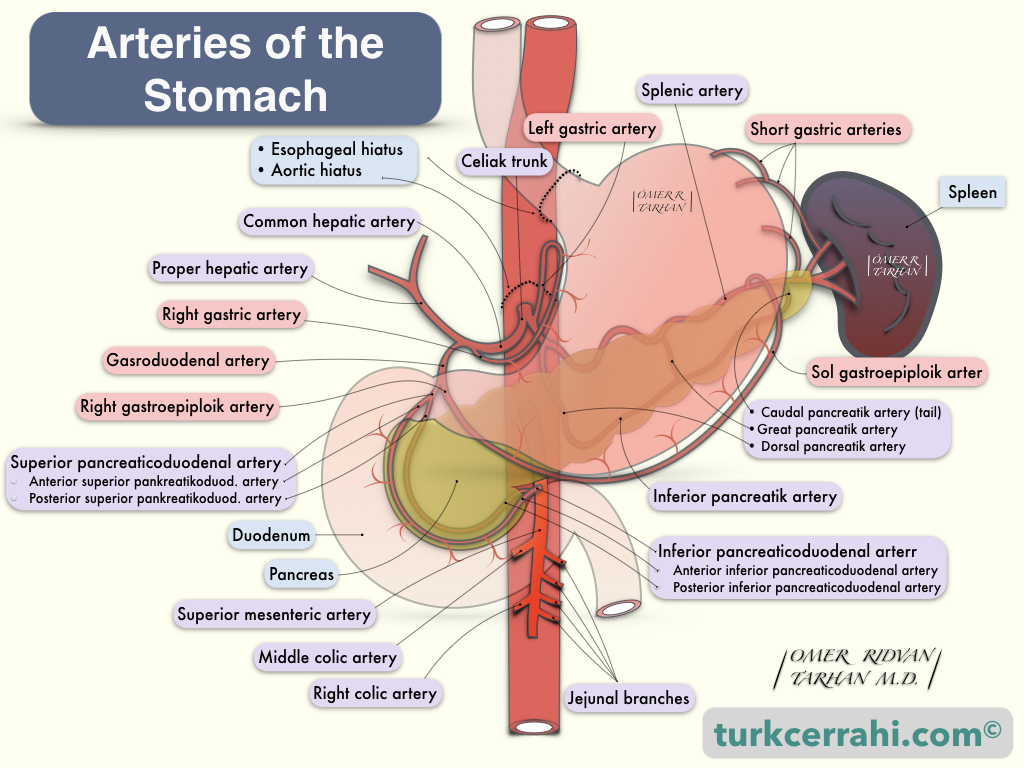

8. Arteries of the Stomach

The stomach is the most richly vascularized portion of the gastrointestinal tract. The stomach has 4 main arteries: the left and right gastric arteries and the left and right gastroepiploic arteries. The stomach will continue to receive blood if one of these arteries is left intact while the other three are ligated. This may be necessary for certain surgical procedures, such as gastric reconstruction after esophagectomy.

Left Gastric Artery (A. Gastrica Sinistra)

It is the smallest branch of the celiac trunk and the thickest artery of the stomach. The left gastric artery feeds the lesser curvature. Truncus coeliacus is close to the incisura angularis. After the left gastric artery arises from the celiac trunk, it goes (up) towards the cardioesophageal junction, then makes a right U-turn from there, runs along the lesser curvature, and joins (anastomoses) with the right gastric artery.

Right Gastric Artery (A. Gastrica Dextra)

It is the first lateral branch of the common hepatic artery. The right gastric artery supplies the lesser curvature of the stomach, and it joins the left gastric artery. The common hepatic artery is a medium-thick branch of the celiac trunk.

Right Gastroepiploic Artery (A. Gastroomentalis Dextra)

The gastroduodenal artery is the second lateral branch of the common hepatic artery. The common hepatic artery continues as the proper hepatic artery after giving the gastroduodenal branch. At the level of the posteroinferior edge of the first portion of the duodenum, the gastroduodenal artery divides into two terminal branches: the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery and the right gastroepiploic artery. The right gastroepiploic artery travels between the first part of the duodenum and the pancreas; it then turns left to enter between the two layers of the greater omentum along the greater curvature of the stomach, where it connects (anastomoses) with the left gastroepiploic artery, which originates from the splenic artery.

Left Gastroepiploic Artery (A. Gastro Omentalis Sinistra)

It is the largest branch of the splenic artery, which arises approximately 1-4 cm proximal to the hilum of the spleen. The left gastroepiploic artery runs from left to right within the gastrosplenic ligament, and then, within the two layers of the greater omentum, approximately 1 cm from the greater curvature of the stomach, anastomoses with the right gastroepiploic artery. The right and left gastroepiploic arteries together supply the greater curvature of the stomach.

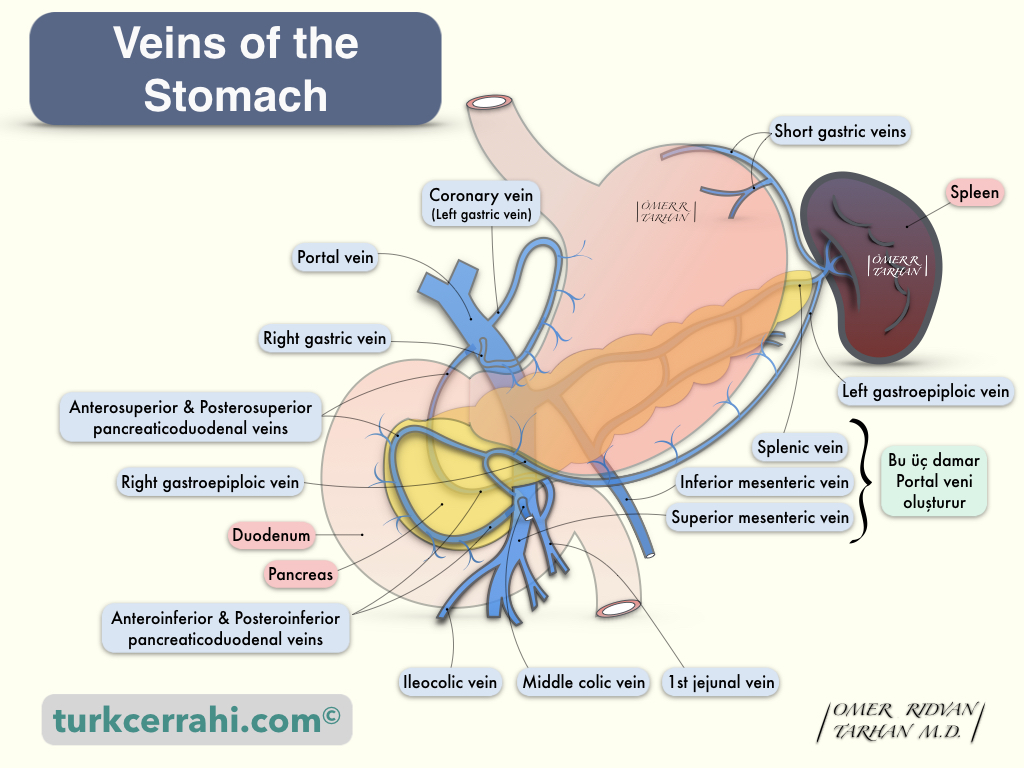

9. Veins of the Stomach

The gastric veins are usually parallel to the arteries. The left gastric (coronary) vein and right gastric vein drain into the portal vein. The right gastroepiploic vein joins the superior mesenteric vein, and the left gastroepiploic vein joins the splenic vein.

10. Clinical Significance of Rich Blood Supply to the Stomach

- Peptic ulcers and gastric cancer can cause massive bleeding.

- The distal splenorenal shunt reduces the pressure of the esophagogastric varices. The splenic vein is cut distal before entering the superior mesenteric vein and sutured to the side of the left renal vein without splenectomy.

- When necessary, two of the four (according to some sources three of the four) vessels of the stomach can be cut without gastric ischemia. For example, the whole stomach with the right gastroepiploic blood supply can be pulled to the neck after esophagectomy (removal of the esophagus).

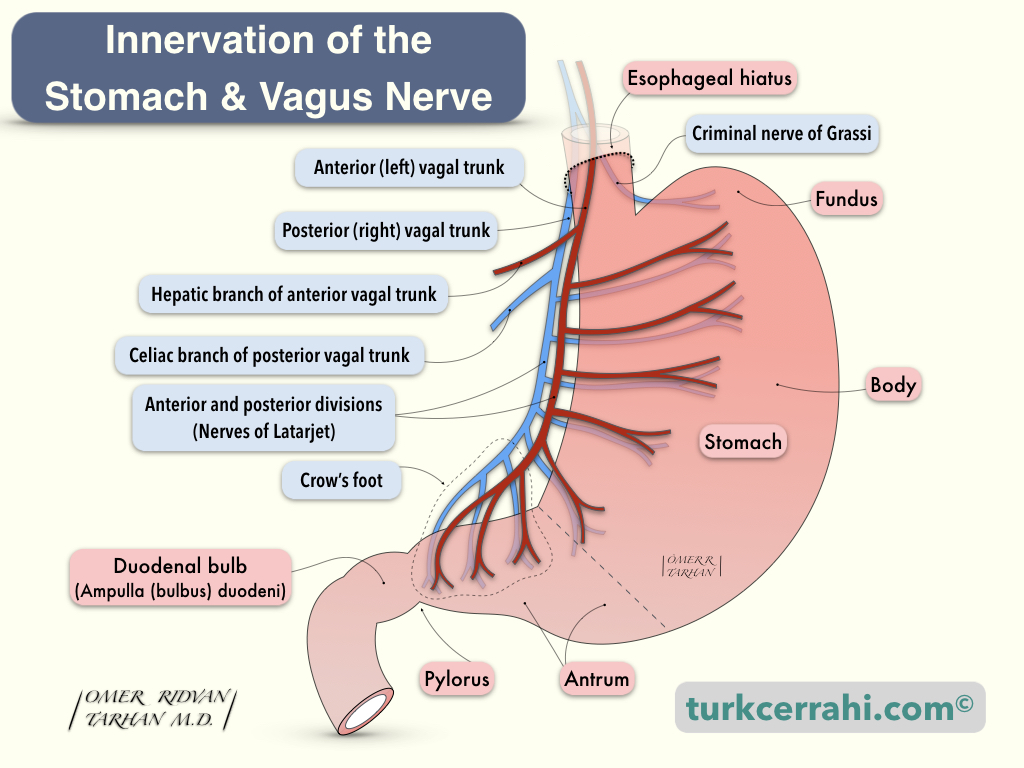

11. Innervation of the Stomach

When the innervation of the stomach is mentioned, the first thing that comes to mind is the vagus nerve, but that's not all. There are both afferent and efferent neurons to the stomach (extrinsic) and a network of nerves inside the stomach (intrinsic; Auerbach myenteric plexus and Meissner's submucosal plexus). All of these nerves together regulate gastric secretion (acid) and motor function (digestion, emptying).

Extrinsic Innervation of the Stomach

- Sympathetic nerves (T5-10 > splanchnic nerves > celiac ganglion > postganglionic sympathetic nerves. Controls the vessels and sphincters of the stomach)

- Parasympathetic nerves (25% of vagus nerve, efferent fibers (from the brain to stomach)

- Sensory nerves (75% of the vagus nerve, control gastric secretion. They are afferent nerves (from the stomach to brain))

Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve arises from the vagal nucleus at the base of the fourth ventricle. In the neck, the vagus nerve runs inside the carotid sheath. When the vagus nerve enters the mediastinum, it gives off the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and the nerve fibers are distributed around the esophagus. At the esophageal hiatus, distributed fibers recombine to form the left (anterior) and right (posterior) vagal trunks (LARP; left anterior, right posterior). At the level of the esophageal hiatus, each trunk gives a branch (hepatic and celiac).

Hepatic and Celiac Branches

The hepatic branch is a branch of the right (anterior) vagus nerve. It runs through the gastrohepatic ligament. The celiac branch is a branch of the left (posterior) vagus nerve.

Latarjet Nerve

After the right and left vagus nerves give off hepatic and celiac branches, they are called the nerves of Latarjet, which continue in the lesser curvature anteriorly and posteriorly by giving branches to the stomach. (André Latarjet, 1877-1947. French anatomist and surgeon, he also performed the first vagotomy.)

Latarjet nerves turn into the crow's foot 5-7 cm from the pylorus, around the incisura angularis.

Criminal Nerve of Grassi

At the level of hiatus, the right (posterior) vagus gives rise to this branch called the criminal nerve of Grassi, which innervates the gastric fundus in some patients (50% according to Schwartz, 90% according to others).

This branch can sometimes emerge above the esophageal hiatus and thus cannot be seen or cut during vagotomy. This leads to the recurrence of peptic ulcers. That's why this nerve is called the “Criminal Nerve of Grassi” (Professor Grassi, Roman Doctor).

Intrinsic Innervation of the Stomach

An intrinsic nervous system, found throughout the gastrointestinal tract and also called the enteric nervous system, is a separate network of the autonomic nervous system. The enteric nervous system has its reflexes (for example, depending on the amount of food (volume) and whether it is liquid or solid).

The enteric nervous system consists of two networks.

- Auerbach's (Myenteric) Plexus: As its name suggests, it lies in the muscularis propria, between the circular and longitudinal muscle fibers.

- Meissner (Submucosal Plexus): Lies in the submucosa layer just below the mucosa.

12. Lymphatic Drainage of the Stomach

The stomach has an extensive lymphatic network, and cancer in the antrum can sometimes spread to lymph nodes in the splenic hilum. Japanese gastric surgeons have demonstrated to the entire world that extensive lymph node dissection (lymphadenectomy) prolongs gastric cancer survival. The lymph node nomenclature shown below demonstrates how important it is. Lymph nodes are typically found around arteries and are given the names of the arteries.

Lymph Node Stations of the Stomach

- Right cardiac lymph nodes

- Left cardiac lymph nodes

- Lymph nodes along the lesser curvature

- Lymph nodes along the greater curvature

- 4sa: Lymph nodes along the short gastric vessels

- 4sb: Lymph nodes along the left gastroepiploic vessels

- 4d: Lymph nodes along the right gastroepiploic vessels

- Suprapyloric lymph nodes ((along the right gastric artery)

- Infrapyloric lymph nodes

- Lymph nodes along the left gastric artery

- Lymph nodes along the common hepatic artery

- 8a: Anterior

- 8b: Posterior

- Lymph nodes around the coeliac axis

- Lymph nodes at the splenic hilum

- Lymph nodes along the splenic artery

- 11d: Distal splenic

- 11p: Proximal splenic

- Lymph nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament

- 12a: Anterior

- 12p: Posterior

- Lymph nodes at the posterior aspect of the pancreas head

- Lymph nodes at the root of the mesenterium

- 14v: SMV (Superior mesenteric vein)

- 14a: SMA (superior mesenteric artery)

- Lymph nodes along the middle colic artery

- Para-aortic group of lymph nodes

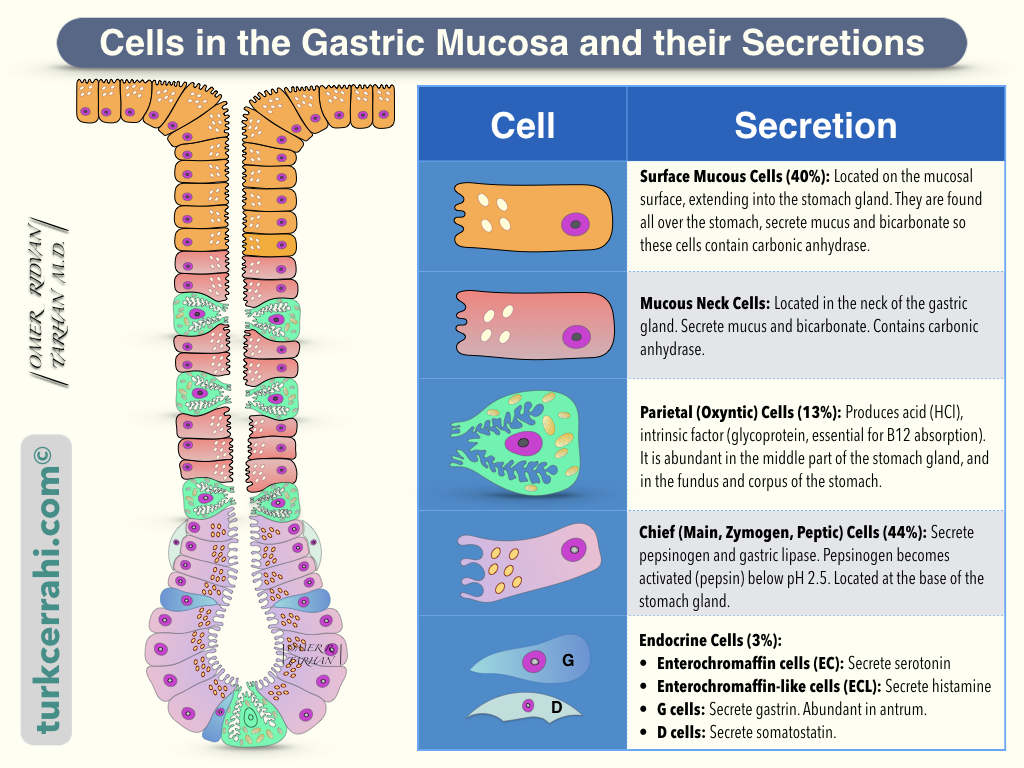

13. Histology of the Stomach

Layers of the Stomach Wall

- Mucosa

- Epithelium (Columnar and Glandular Epithelium)

- Basal Membrane (Basal Lamina + Reticular Lamina)

- Lamina Propria

- Muscularis Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscularis propria

- Serosa (visceral peritoneum)

Cells and Structures of the Gastric Mucosa

On scanning electron microscope images, the gastric mucosal surface resembles the surface of a perforated sponge. The surface is velvety, and the holes represent the openings of the gastric glands.

A. Mucus-Secreting Cells (Surface Mucous Cells) (40%)

They form the velvety surface of the stomach. It covers the entire inner surface of the stomach. Surface mucous cells extend into the stomach glands as well. They produce mucus and bicarbonate, which protect the gastric mucosa from acid, pepsin, and irritants. Carbonic anhydrase, a ubiquitous enzyme found in mucus-secreting cells, catalyzes the production of bicarbonate.

B. Gastric Glands (57%)

The structure and secretory content of the gastric glands differ depending on their location in the stomach. The cardia's gastric glands are superficial, branched, and complex like trees. They secrete mucus and bicarbonate.

The fundus and corpus gastric glands are simple tubular and deeper. Parietal cells are abundant in the fundus and corpus (acid ↑).

As in the cardia, the antrum's gastric glands are superficial, complex, and branched. In the antrum, acid-producing parietal cells are scarce, while G and D cells are abundant (gastrin and somatostatin).

Parietal (or oxyntic) cells (13%) produce acid (HCl), intrinsic factor (glycoprotein), and bicarbonate (HCO3). Intrinsic factor is essential for B12 absorption from the terminal ileum.

Parietal cells have the following receptors leading to acid secretion

- H2 receptor (histamine binds)

- M3 receptor (acetylcholine binds)

- CC2 receptor (gastrin binds)

- M receptor (muscarinic).

The proton pump (H+/K+ ATPase) in tubulovesicles in parietal cells pumps acid into the vesicle despite a concentration difference of 1/3 million, which requires intense energy and a large number of mitochondria (notice the large number of mitochondria in this cell).

Acid-stimulating substances such as histamine and gastrin bind to cell membranes, causing vesicles to open and acid to be secreted.

Parietal cells (also known as oxyntic cells) are found in the mucosa of the fundus and corpus of the stomach in the gastric glands.

Chief cells (main, zymogen, or peptic cells) (44%) secrete pepsinogen-I and II as well as gastric lipase. Pepsinogen, an inactive enzyme, namely a zymogen, is activated below pH 2.5. The chief cells are located at the base of the gastric glands. Chief cells, like other enzyme-secreting cells of the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., pancreatic acinar cells), contain abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum and large, dense zymogen-containing granules at the cell’s apex.

C. Endocrine Cells (3%)

- Enterochromaffin Cells (EC): Secrete serotonin

- Enterochromaffin-like Cells (ECL): Secrete histamine

- G Cells: Secrete Gastrin

- D cells: Secrete somatostatin

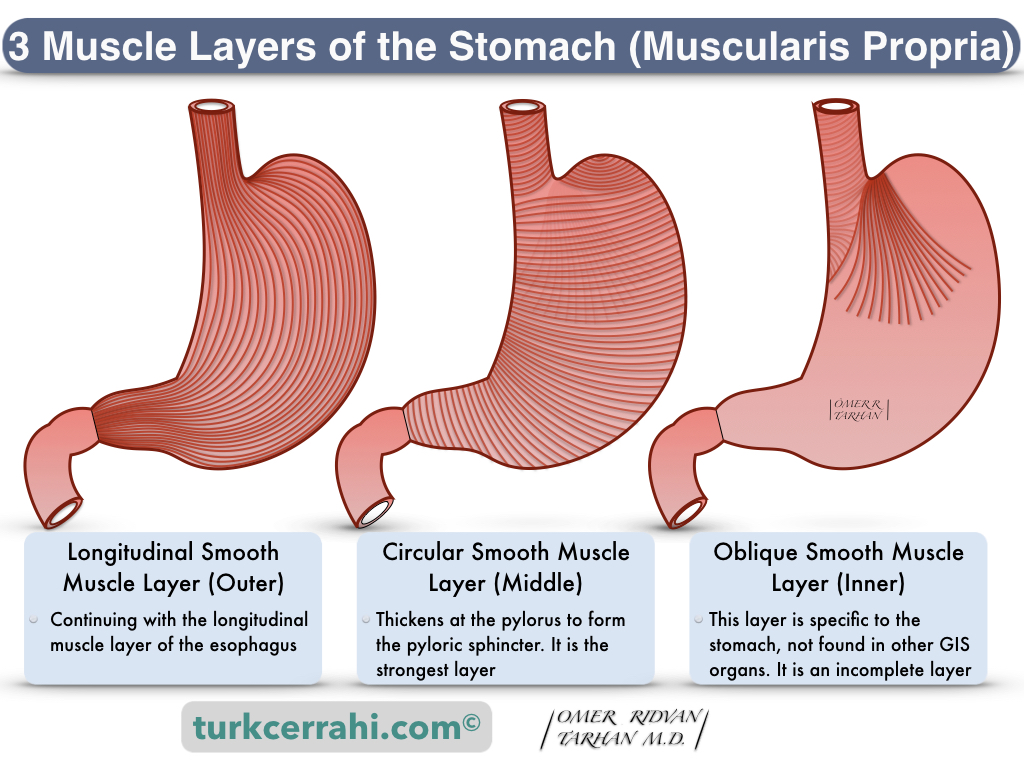

Three Muscle Layers of Stomach (Muscularis Propria)

- Oblique Layer (Inner): It is complete in fundus and corpus, fibers become sparse and disappear towards the antrum.

- Circular Layer (Middle): It continues with the circular muscle layer of the esophagus proximally and the pylorus distally.

- Longitudinal Layer (Outer): It continues with the esophageal longitudinal muscle layer proximally and the duodenum distally.

Serosa of the Stomach

The gastric serosa is the outermost layer of the stomach (visceral peritoneum). It is composed of a layer of simple squamous epithelium, known as mesothelium, and a thin layer of connective tissue underneath. In gastric cancers, cells that extend beyond the serosa spread into the abdominal cavity.