Anatomy of the Gallbladder

Overview

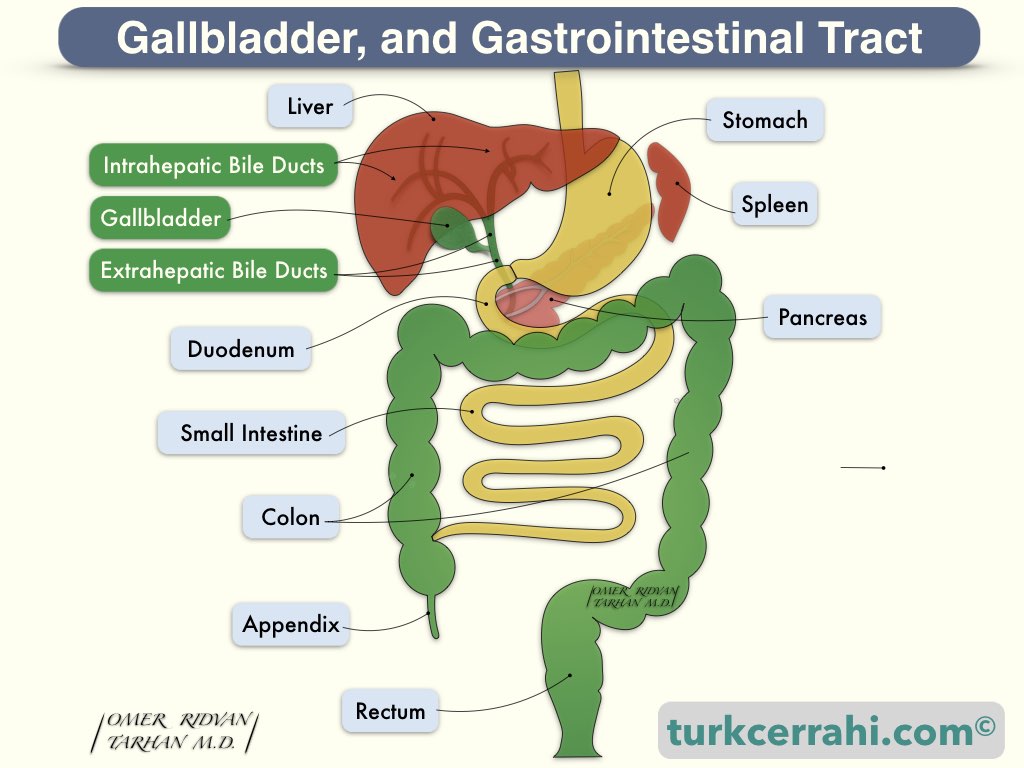

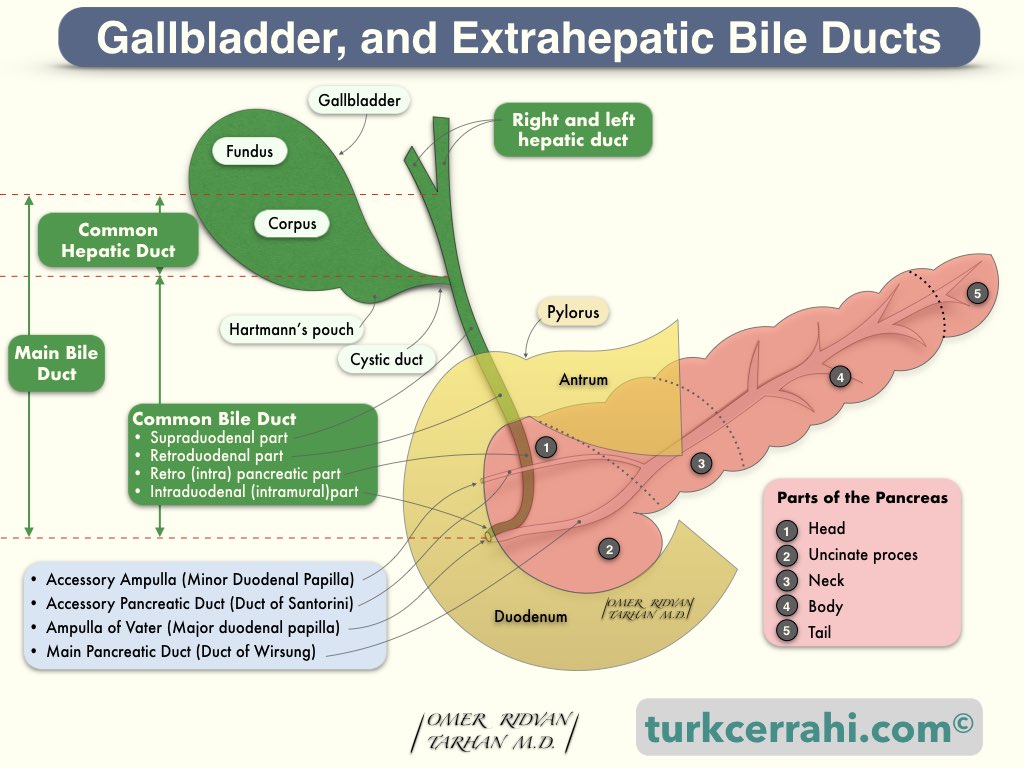

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped sac with a length of 7-10 cm and a capacity of 30–50 mL. The gallbladder is attached to the anterior and inferior surfaces of the liver, between the right (segment V) and left liver lobes (segment IVb, namely the quadrate lobe). The gallbladder has four parts: the fundus, corpus, infundibulum, and neck.

The upper part of the gallbladder is attached to the liver. Sometimes the part where the gallbladder is attached to the liver is very narrow, and the gallbladder is more mobile. In other words, the gallbladder has a mesentery that is prone to torsion. Sometimes the gallbladder is embedded in the liver parenchyma (intrahepatic gallbladder).

The gallbladder is lined by a simple columnar epithelium, similar to intestinal epithelial absorptive cells. In other words, the gall bladder epithelium includes only this single cell type (columnar cells).

The intestinal epithelium is composed of absorptive enterocytes (columnar cells, absorption), goblet cells (mucus- and peptide-production), Paneth cells (secretion of antimicrobial peptides), microfold (M) cells (antigen sampling), and enteroendocrine cells (hormone production).

In contrast to other hollow gastrointestinal organs, the gallbladder lacks muscularis mucosa and submucosa.

Mucosal folds in the gallbladder neck act as valves (the spiral valves of Heister) and make cannulation and catheterization difficult. Cannulas are rigid and usually made of metal, while catheters are flexible and usually made of plastic or silicone.

Cystic Duct

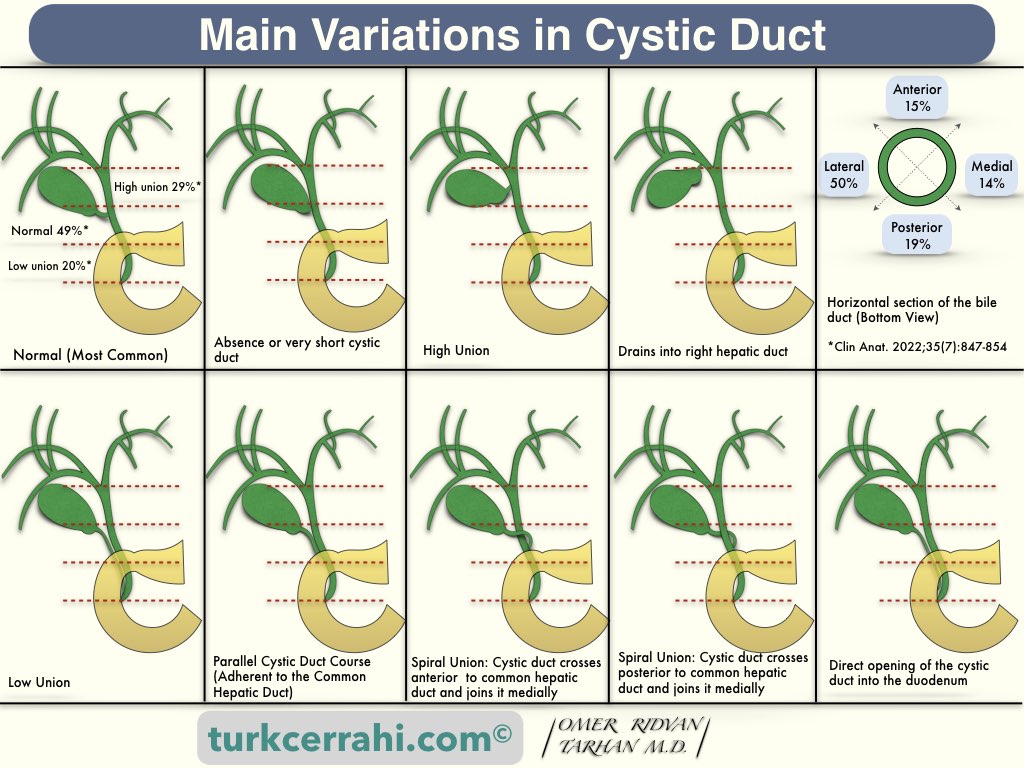

The cystic duct is approximately 3 mm in diameter. Its length varies between 2-4 cm, depending on the type of union with the common hepatic duct. The cystic duct usually (80%) joins the main hepatic duct above the duodenum. Rarely, the cystic duct may be absent.

The point of insertion of the cystic duct into the CHD is variable. According to a study of MR cholangiography, the level of the union of the cystic duct to the bile duct was proximal in 29%, middle in 49%, and distal in 20%. In the same study, the cystic duct orifice was 50% on the lateral surface of the bile duct, 19% posterior, 15% anterior, and 14% medial. In other words, the cystic duct usually enters the CHD from the right lateral side, roughly halfway between the hepatic confluence and the ampulla of Vater. Rarely, the cystic duct opens directly into the duodenum.

Cystic Duct Variations

- Absence or very short cystic duct

- High union with common hepatic duct

- Drains into the right hepatic duct

- Low union with common hepatic duct

- Parallel cystic duct course (adherent to common hepatic duct)

- Spiral union with common hepatic duct (anterior, posterior, or medial)

- Direct opening of the cystic duct into the duodenum (very rare)

Arteries of the Gallbladder

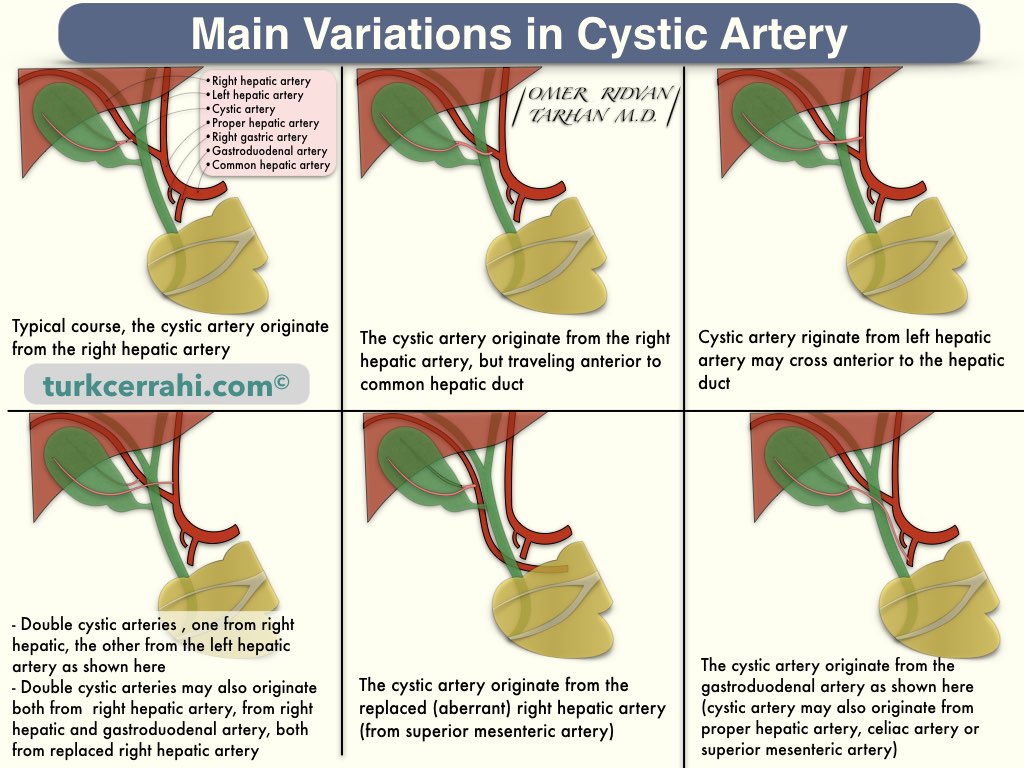

Cystic Artery Variations

The gallbladder and cystic duct are supplied by the cystic artery, which originates from the right hepatic artery (75-90%) within Calot's triangle. In other words, the cystic artery is part of the contents of the Calot triangle. Variations of the cystic artery are common:

- Double cystic artery

- Both originate from the right hepatic artery

- One of the arteries may arise from the proper or common hepatic artery, left hepatic artery, or gastroduodenal artery

- Cystic artery crosses anterior to the common bile duct or common hepatic duct

- Origin of the cystic artery may vary:

- Common hepatic artery

- Left (branch of the) hepatic artery

- Gastroduodenal artery

- Replaced right hepatic artery

- Superior mesenteric artery

- Celiac axis

- Directly from liver parenchyma

Veins of the Gallbladder

The gallbladder's venous drainage travels through the gallbladder bed via a network of numerous small veins that empty directly into hepatic vein branches within the liver parenchyma. In other words, the cystic vein is usually absent. When present, the cystic vein drains into the right branch of the portal vein, accompanying the cystic duct.

Lymph Nodes of the Gallbladder

The lymphatics of the gallbladder drain into the cystic duct node, located at the junction of the cystic duct and common hepatic duct, also called the Lund node. The cystic duct node drains primarily into the hepatic lymph nodes and, ultimately, the coeliac lymph nodes. Lymphatic vessels from the hepatic surface of the gallbladder may also communicate with lymphatic vessels within the liver.

The cystic duct node is the sentinel lymph node of the gallbladder, also called Lund’s node (cystic lymph node of Lund) or Mascagni’s lymph node.

Nerves of the Gallbladder

The gallbladder receives parasympathetic, sympathetic, and sensory innervation.

- Parasympathetic nerve supply from the right vagus through its hepatic branch

- Sympathetic supply comes from T 7-9 through the celiac plexus.

- Sensory information from the gallbladder (pain of the biliary colic) passes through the splanchnic nerves via sympathetic afferent fibers. According to some other sources, sensory information is carried by the right phrenic nerve.

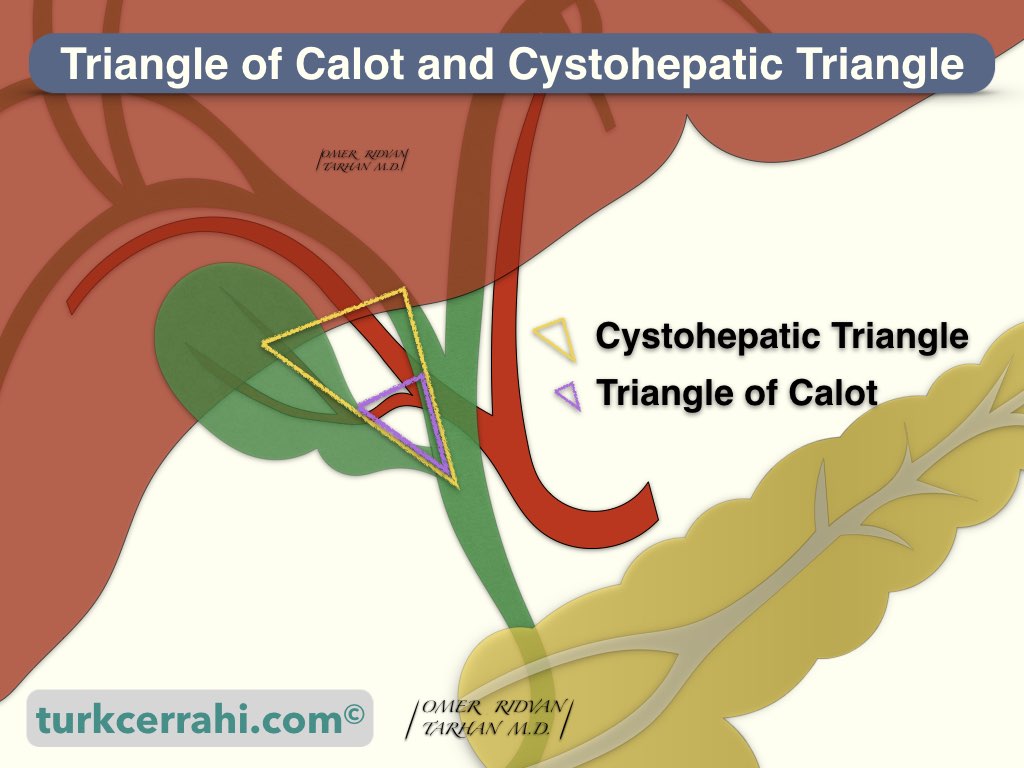

Hepatocystic Triangle

The hepatocystic triangle (cystohepatic triangle) is formed by the cystic duct, the common bile duct, and the edge of the liver.

Triangle of Calot

The Calot triangle is formed by the cystic duct, common bile duct, and cystic artery.

Importance: While performing gallbladder surgery, these triangles are revealed and dissected.

The Function of the Gallbladder

The gallbladder stores bile produced by the liver and concentrates it by absorbing water. After meals, the gallbladder contracts and empties the bile into the duodenum. Gall is an Anglo-Saxon word for bile. Despite its name, the gallbladder does not produce bile itself.

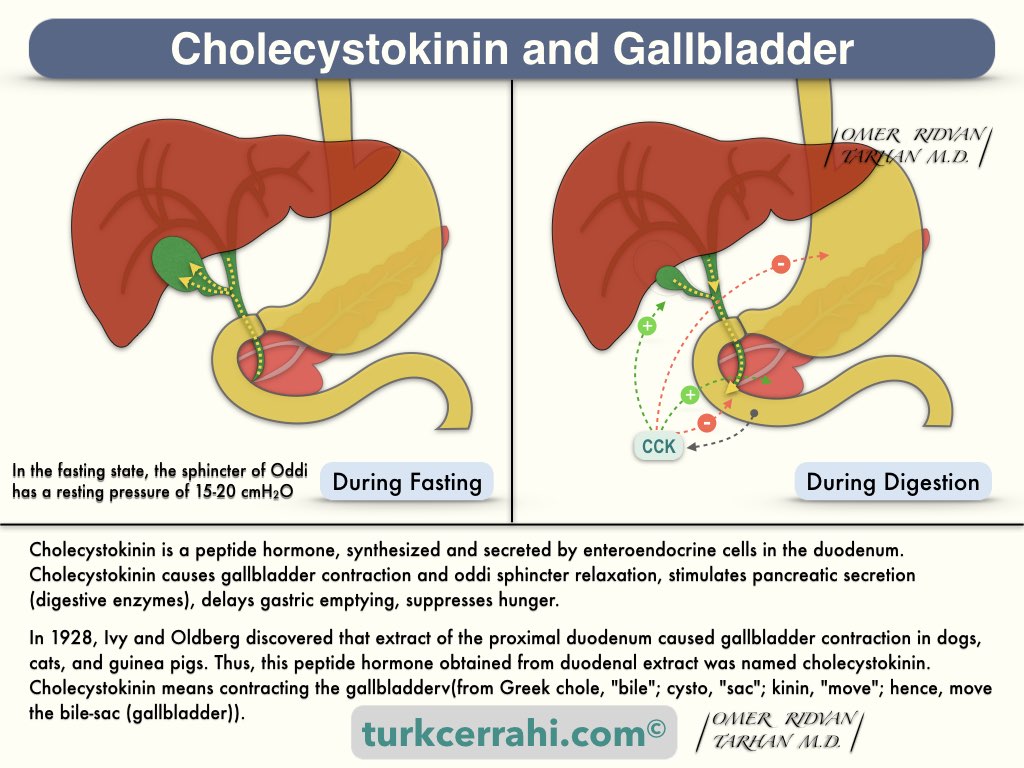

During fasting, the sphincter of Oddi maintains a constant (resting) pressure and directs bile to the gallbladder.

Following a meal, in response to antrum distension, the vago-vagal reflex causes gallbladder contraction and relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi (the gastric phase of digestion).

When partially digested food (amino acids and peptides) reaches the duodenum, a peptide hormone (cholecystokinin, CCK) is secreted from the duodenum into the blood. CCK causes relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi, contraction, and emptying of the gallbladder.

The vagus nerve also causes the contraction of the gallbladder, which is mediated by CCK. Therefore, the effect of cholecystokinin on the gallbladder is reduced in vagotomy patients. Consequently, vagotomy increases the volume of the gallbladder and the incidence of gallstones.